—Rodrigo Camarena González, ITAM

[Editors’ Note: This is Part 4 of a symposium on the recent constitutional amendments affecting the judiciary in Mexico. The introduction to the symposium can be found here. The symposium pieces are cross-posted at ICONnect (in English) and at IberICONnect (in Spanish). We are grateful to Ana Micaela Alterio for her work in organizing the symposium.]

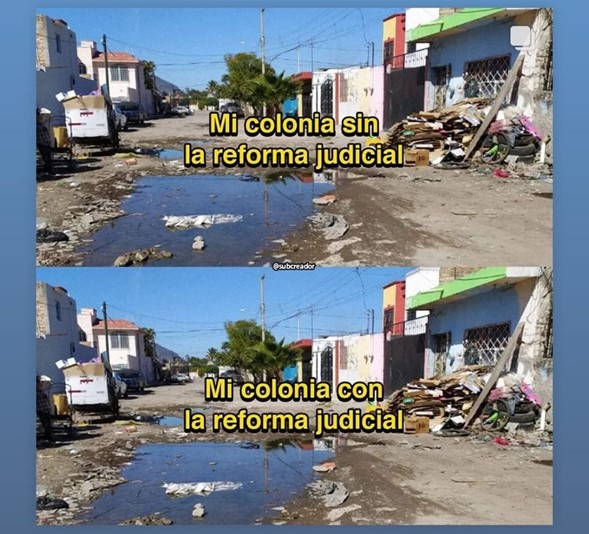

This meme[1] captures the feelings of a part of the Mexican population about the judicial reform. Many people do not accept the Morenista slogan that by firing all the country’s judges and opening the judiciary to popular vote, the country will be a better place to live. However, neither do they buy the argument of some judges that Mexico is transiting to totalitarianism, a regime in which “individuals are a [means] for the benefit and development of the state, and not the state is the means to guarantee the rights of the governed.” For this sector, the reform is a mere dispute between elites. For them, the amendment does not aggravate Mexican daily life; neighborhoods will continue to be abandoned, with unsafe streets, potholes and no access to drinking water.

But, in reality, does the reform make a difference? In a Mexico with 116,000 disappeared persons, 13 feminicides per day, state ecocides, 50 million impoverished people and structural racism, doesn’t the reform aggravate the situation? If it was already impossible to speak of “democracy”, does the reform contribute to a qualitative change towards an even more authoritarian regime? What do the process and content of the reform tell us about the person-power relationship? Think of the searching mother who goes to the prosecutor’s office, the working person who demands her right to water, the racialized woman who resists militarization. These people interact with entities, public or private, capable of conditioning, restricting, or brutalizing their bodies and lives through physical, economic, or discursive violence. How does the constitutional change affect them?

To begin with, the reform process was exclusive and indolent. Despite the conventional mandate of prior consultation, the Congress never consulted indigenous peoples, Afro-descendants or people with disabilities. Thus, they ignored the indigenous jurisdiction, rejected anti-racist judicial powers, anti-ableist visions, and everything that non-dominant normative systems could contribute. Moreover, they never invited searching mothers to share their feelings about police, prosecutors or courts. In fact, as it was said in social networks, “the prosecutors’ offices were not even touched with the petal of a reform”.

By contrast, how does it leave the executive? Along with hyper-presidentialism, today, we have omnipresent militarism. Thanks to the support or submission of presidents of the PRI, PAN and MORENA, the armed forces have not only expanded their powers in security, they now control the entire public administration. Today they build roads, administer airports, and even build hotels and casinos in archeological zones. Despite their direct responsibility in the forced disappearance of the 43 from Ayotzinapa, the public perception of the military is still relatively good, perhaps because of the discipline they project, or because they are one of the few options for social mobility. This militarized executive will now be “countered” by a popularly voted judiciary.

And the legislature? There is nothing more cynical than for a legislator to approve this “anti-corruption” reform in exchange for not having arrest warrants executed for his involvement in a pedophile ring. The following day, the Oaxaca legislature approved, unanimously, in 6 minutes, without debate or analysis, a 312-page opinion. In two days, 21 local legislatures joined in. If the process tells us anything, it is that there is a gulf between legislators and students and judicial workers. Imagining a meeting space as an open parliament, or, in general, influencing legislators is impossible. Ironically, the judiciary was the one that forced legislators to do the basics: read before voting or respect the agenda.

Then, the judiciary. The reform accuses the judiciaries of being corrupt and inaccessible elites that stand in the way of transformation. On the one hand, most trials in the country are at the state level, not the federal. However, the reform ignores the fact that the federal judiciary is often better evaluated than local ones and ignores root problems of the local one, such as its lack of budget. Worse yet, there is no causal link between the popular vote and the reduction of corruption; it is precisely the parties that generate the least trust. An alternative would have been better procedural, administrative or citizen controls. On the other hand, the reform does not make justice more accessible. The Amparo procedure is still extremely complex and cumbersome, which makes it expensive. Nor does it balance economic inequalities with better public defenders. The reform also eliminates the two Chambers of the Court where most Amparos were resolved, saturating and mediatizing the Plenary even more, and hindering constitutional justice. Thus, the judges will be dismissed, but rights protection will not be improved.

How did this reform relate to the “market”? AMLO did not summon mothers to discuss the reform, but he did summon the five wealthiest people in the country. Although MORENA claims to be leftist, it did not activate its machinery for a redistributive fiscal reform. Judicial reform was a priority, but not so much the reduction from 48 to 40 working hours, in the country where people work the most globally. In fact, the new president said that the reduction would depend on the consensus of businessmen. Perhaps MORENA will keep the 40-hour “card” for when it wants to put military personnel in the central bank. It depends on the bankers whether a working person rests on Saturdays, but it does not depend on the victims’ movements the shape of the justice system.

What about other informal powers? The reform tailors robes for them. If the president of MORENA is already accused of selling municipal candidacies, what will happen when the black market includes seven thousand judicial positions? If the organized crime already threatens, assassinates, or places officials in municipalities, legislatures, governorships and even federal departments, what can we expect it to do in an inscrutable judicial election? If we had a narco-state, now we will have narco-jurisprudence.

With this “democracy” in mind, let us take the case of the people of Xochimilco as an example. A few days ago, Mexico City’s and the county’s government repressed the people in a peaceful demonstration. With the previous legal framework, the organized people were able to file an Amparo before an independent federal judge and were able to stop the installation of a military cartel. With the new framework, the National Guard (NG) can detain protesters, charge them with a crime before a “faceless” military judge and give them automatic preventive detention.

So, things are indeed worse for the neighborhood. The amendment not only created a triple legitimacy problem that haunts us lawyers (if all branches are popularly elected: who has the last word?), but it worsens the situation in general. If we fall into a pothole and sue the city council, it doesn’t matter because the reform does not touch the administrative courts. However, if we have the misfortune to go to a prosecutor’s office, we will not only have an overburdened prosecutor, but also a judge sponsored by the narco. Or, if we file a lawsuit to have water, we will have a judge sponsored by Coca-Cola.

What kind of regime do we have now? Perhaps the duality of the totalitarian state: rules for the circulation of capital, and arbitrariness in many other scenarios. But it seems that categories like “democratic backsliding” don’t apply because there never was a popular government. Perhaps we will come up with more precise labels. What I am sure of is that we must organize and articulate ourselves to resist this reform, as well as that of the NG and the reform of the automatic preventive detention that together form an authoritarian whole.

Suggested citation: Rodrigo Camarena González, Symposium on the Judicial Overhaul in Mexico Part 4: The Mexican Judicial Reform — So What? Int’l J. Const. L. Blog, Oct. 3, 2024, at: http://www.iconnectblog.com/symposium-on-the-judicial-overhaul-in-mexico-part-4-the-mexican-judicial-reform-so-what/

[1] The first picture indicates “my neighborhood without judicial reform,” while the second shows “my neighborhood with judicial reform.”

Comments

One response to “Symposium on the Judicial Overhaul in Mexico Part 4: The Mexican Judicial Reform — So What?”

[…] Puedes encontrar la entrada homóloga en ICONnect aquí. […]