—Yuliya Kaspiarovich, IE University, & Evan Rosevear, University of Southampton

During its first ten years, the International Society of Public Law (ICON-S) has become a leading community for all areas of public law. Not only is it a society with truly global reach, but it is also in constant development through regional chapters and interest groups. The success of ICON-S is at its apex during annual conferences (Florence 2014, New York 2015, Berlin 2016, Copenhagen 2017, Hong Kong 2018, Santiago de Chile 2019, ICON-S Mundo online 2021, Wrocław 2022, Wellington 2023). This year, the annual ICON-S conference will be hosted by the IE University Law School in Madrid on July 8-10.

Every year, the Call for Papers issued for the annual conference invites proposals for formed panels and individual submissions from academics and practitioners at all career stages. The individual submissions are organized into panels by the ICON-S team. This year, we were tasked with this responsibility. During the process, we noticed several patterns that may be of some interest to public law scholars with respect to the development of the Society during its first decade, its future, and the broader issue of equity, diversity, and inclusion in academia.

In addition to the record number of fully formed panels submitted for consideration, we received 528 papers. Of these, 233 (44%) were submitted by women[1] and 123 (23%) were submitted by scholars based at institutions outside of the OECD. ICON-S is also a multilingual society, and this annual conference is held in Spain, 33 (6%) of the papers were submitted in Spanish. With respect to seniority, 176 (33%) papers were submitted by students and postdoctoral researchers, 165 (31%) by those at the assistant professor or lecturer level, 65 (12%) by associate professors, senior lecturers or readers, and 122 (23%) by those at the rank of full professor or higher.[2] Considering the two dimensions together, we were pleased to see that the gender breakdown across seniority does appear to be approaching parity in the more junior ranks. It is also notable that papers were received from individuals based at institutions in over 60 countries. The most common countries of origin were: Poland (42); Brazil (40); UK (37); Italy (36); Spain (36); and USA (36).

| Table 1. Gender by Seniority and Institution Country | Female | Total | |

| n | % | ||

| Students & Postdocs | 79 | 45% | 176 |

| Assistant Professor/Lecturer | 80 | 48% | 165 |

| Associate Professor/Sr. Lecturer | 30 | 46% | 65 |

| Professor | 44 | 36% | 122 |

| Non-OECD | 61 | 50% | 123 |

| OECD | 172 | 42% | 405 |

Our reader is most certainly curious to find out how we assembled panels from 528 very diverse individual submissions. Our methodology consisted of several steps. Based on an initial review of the applications, we identified the gender, region, and academic rank of each submitter. At the same time, each paper was identified as relevant to between one and three topics. The list of topics was developed reflexively, using a combination of deductive and inductive categorisation and those assigned to at least 25 papers are reported in Table 2, along with numbers submitted by female and non-OECD scholars. We then separated the papers into subgroups of roughly equal size based on their assigned categories. Finally, we constructed the panels from within these subgroups, taking into consideration gender representation as well as the desirability of variation in seniority and, as appropriate, region.

This process resulted in the creation of 94 panels: 36 with 5 papers and 58 with 6 papers. None were composed solely of men, and one was composed solely of women. 16 panels (17%) had one woman, 39 panels (41%) had two women, and the remainder had three or more women. Concerning the seniority of applicants, 69 (73%) panels were to be chaired by full professors and the rest by associate or assistant professors. These numbers, of course, represent the preliminary program; as with any conference, there are sure to be cancellations and modifications.

Table 2. Thematic Categorisation by Gender and Institution Country

| Topic | Female | Non-OECD | Total |

| AI & Technology | 60 | 32 | 123 |

| Democratic Processes & Institutions | 48 | 39 | 122 |

| European Union | 31 | 3 | 80 |

| Courts & Judges | 35 | 19 | 73 |

| International Human Rights | 41 | 15 | 69 |

| Constitutional Theory | 24 | 10 | 68 |

| Constitutional Interpretation | 24 | 21 | 58 |

| Climate Change | 21 | 11 | 48 |

| Administrative Law & Regulation | 17 | 16 | 47 |

| Constitution Making & Design | 18 | 8 | 45 |

| Conflict & International Criminal Law | 18 | 4 | 33 |

| Economic & Social Rights | 18 | 11 | 32 |

| Sustainability & Resilience | 16 | 5 | 26 |

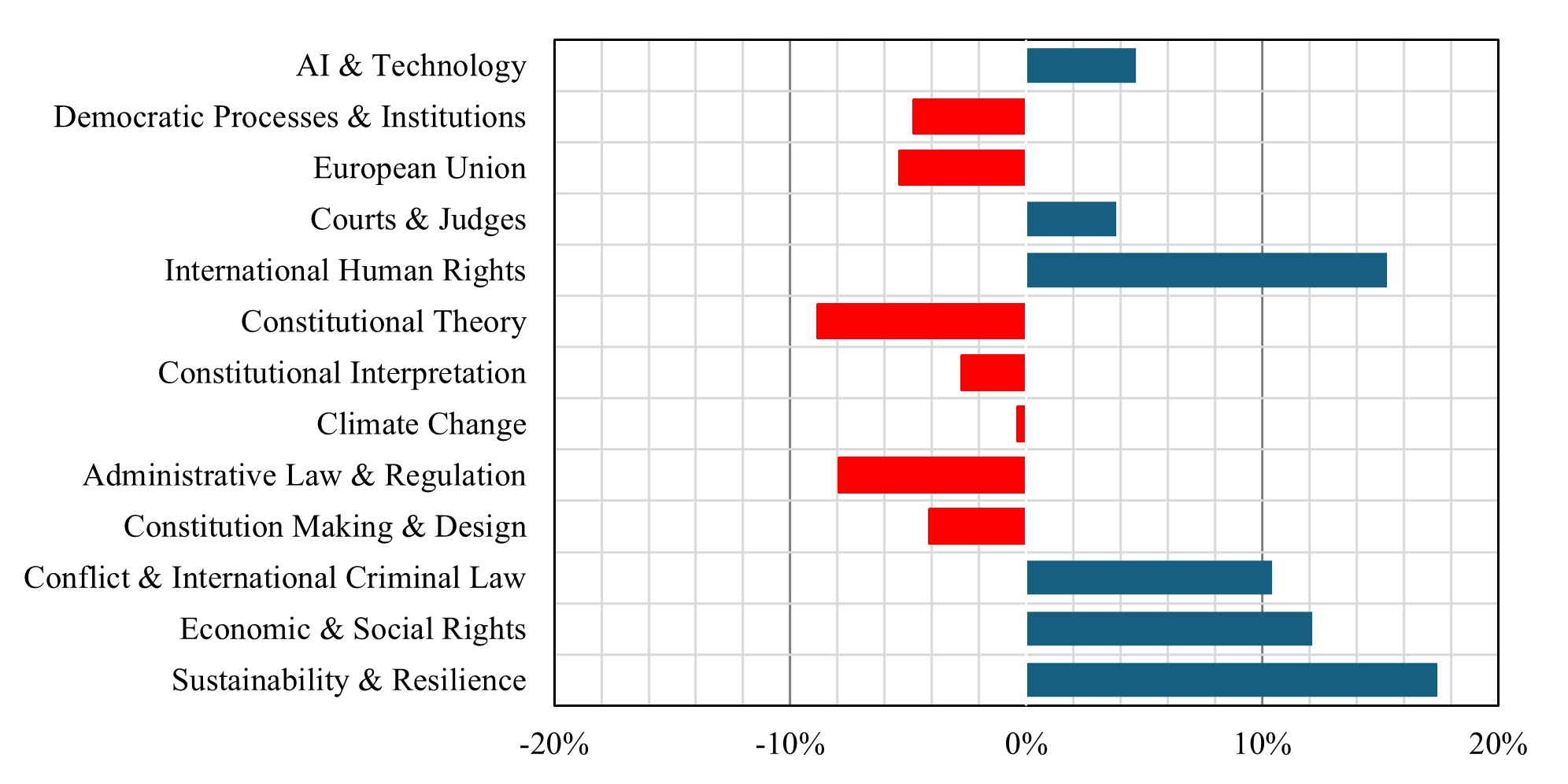

While completing this task, we noticed an interesting correlation between gender and topics, suggesting the possible existence of gendered research agendas.[3] This trend is reflected in Figure 1, which shows the difference between the proportion of papers for a given topic that would be expected if there were no systematic difference between female and non-female submitted papers (44%, the overall percentage of female-submitted papers) and the actual percentage of papers submitted by female authors for a given topic. A positive (blue bar) indicates a higher-than-expected percentage of female-submitted papers, and a negative (red bar) indicates a lower-than-expected percentage.

Papers submitted by female authors are over-represented in a number of topic thematic areas, including international human rights, economic and social rights, and sustainability. On the other hand, papers submitted by male authors dominated several topics, including constitutional theory and administrative law. We also noticed that there is a slight overrepresentation of papers proposed by female authors in the AI & Technology category.

Figure 1. Expected vs Actual Number of Papers Submitted by Female Authors

Finally, while the process was fascinating for both of us, we also recognize the possibility for inaccurate characterization introduced by the third-party identification of subject matter, particularly when the sole basis for evaluation is a brief abstract. As such, we would humbly submit that it may be desirable for future conferences to allow applicants to identify 2-3 predefined thematic areas with which their proposed panel or paper aligns. Such a list might reasonably be assembled in relation to existing interest groups by drawing on the expert knowledge of the ICON-S Council or some other method to be determined by the Secretariat. This would, we believe, enable us to deal with a growing volume of submissions in the most effective way and respect your individual expectations.

See you in Madrid in July!

Suggested citation: Yuliya Kaspiarovich and Evan Rosevear, Statistics on Individual Submissions for the 2024 Annual ICON-S Conference, Int’l J. Const. L. Blog, May 29, 2024, at: http://www.iconnectblog.com/statistics-on-individual-submissions-for-the-2024-annual-icon-s-conference/

[1] Gender was classified on the basis of self-identification (eg, the use of Ms or Mrs as a title) if present, or on the basis of the given name(s) used by the submitting author in the application form. This does introduce the possibility of error due to mixed gender authorship in cases of multi-authored papers. However, only 65 (12%) of the 528 papers had more than one author.

[2] Seniority was assigned on the basis of the submitter’s self-reported academic title in the application form.

[3] Ellen M Key and Jane Lawrence Sumner, ‘You Research Like a Girl: Gendered Research Agendas and Their Implications’ (2019) 52 PS: Political Science & Politics 663.

Comments